March 8, 2016

Increasingly, an adequate supply of drinking water is an issue facing communities around the globe, from western areas in the United States that have experienced droughts, in particular California, to developing nations whose populations are rapidly moving into urban areas, according to a recent United Nations report.

In response to those challenges, interest in rainwater catchment systems as a source of drinking water continues to grow. According to the American Rainwater Catchment Systems Association, a survey of the US rainwater harvesting market revealed “substantial growth in the face of an otherwise stagnant economy.”

A recent UL whitepaper outlines the benefits of rainwater catchment systems and how they are tested for safety. UL is being asked now to certify a growing number of such products used in the United States and Canada.

“These catchment systems are really catching on, for residents and building owners,” said Jason Carlson, a UL staff chemist. “This is a new area that helps with LEED construction point recognition by reducing overall water demands for a building and reduces storm water runoff.”

Rainwater catchment systems consist of four major parts:

- Collection area: Almost always, the roof of a building.

- Transport system: Gutters and downspouts, which direct the water into the holding container. Pumps and standard plumbing components such as pipes, fittings, valves, gaskets, and sealants move water on-demand from the holding container to where it will be used.

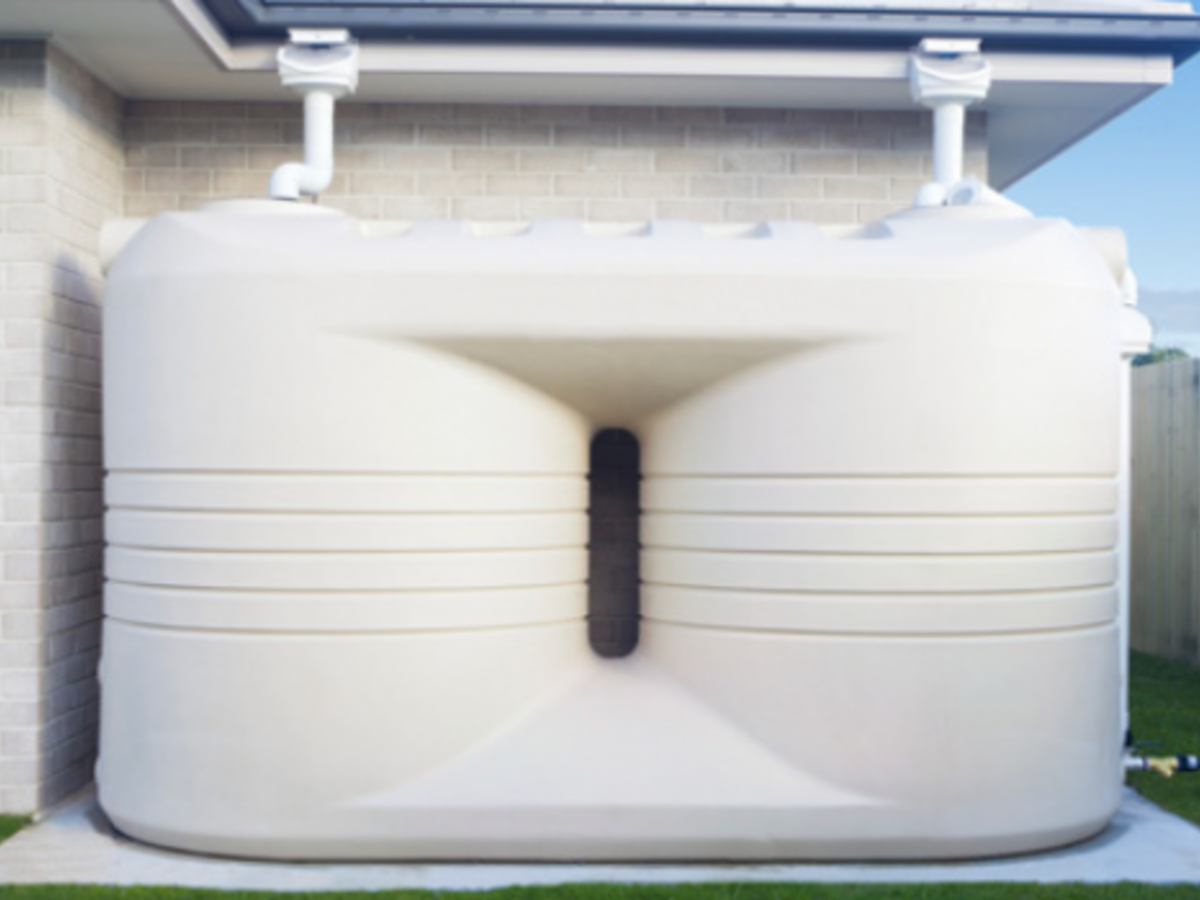

- Container: A large cistern or tank typically, which can often hold thousands of gallons of water.

- Final treatment system: Before the water can be used as drinking water, micro filtration and ultraviolet (UV) or chemical purification is required.

When it comes to catching rainwater for human consumption, the very first step in the process, when the rain drops land on the roof, can pose immediate health risks. These risks come from local environmental factors and from the roofing material itself.

“Roofs get dirty, from bird droppings to leaves, even though rainwater is generally very clean,” Carlson said. “We not only look at the health effects of what chemical contaminants a roofing material leaches, but also if the roofing material promotes microbial growth, which is not something you want added to your catchment system.”

In addition, UL tests collections surfaces for the extraction of harmful contaminants under the influence of the nearly pure state of rainwater, along with how this changes over time from UV light exposure.

“Very pure water is actually a harsh compound compared to the water coming from municipal water systems, which is almost always treated with chlorine, pH adjusted and buffered and enhanced with fluoride,” said Stephen Woynerowski, a UL staff chemist. “In the pure state, water may bind to other chemicals that are present, which could strip chemicals from the roof and other materials that make up the catchment systems.”

UL certifies rainwater catchment products, from roofing materials to cisterns, for potable use against the applicable requirements detailed in NSF International’s 61 and P151 standards. Standards for water purification systems are handled separately. In addition, UL also tests some systems for non-potable use, such as cleaning or watering inedible plants.

In the lab, UL scientists must determine the exact size of the test sample and the amount of water used. Their calculations determine the ratio of the surface to water, in order to mimic real-life conditions.

The testing occurs at UL’s Northbrook, Ill. facility, which houses rows of containers filled with soaking products and materials. The UL teams submerge the sample pieces that are part of the catchment systems in water overnight, and then replace the water, again and again for a period of up to two weeks. At the end of this period, the water is tested for trace amounts of chemicals to determine the safety of the water contact product.

In addition, some of the products or materials, such as paint, will first be exposed to UV radiation, to simulate real-life sun exposure. In some tests, UL places the products in the Arizona desert for an extended period of time.

“Our service to test rainwater catchment systems builds on the years of work we have been doing to certify components for municipal water systems, individual wells and water treatment plants,” Carlson said. “In this case, we are certifying all the components from the roof to the tap.”

For more information on UL’s testing and services, visit: https://www.ul.com/water.